THE CUROUS MOANING OF KENFIG BURROWS

A multi-disciplinary work inspired by the life and work of Victorian astronomer and photographer Thereza Dillwyn Llewelyn, and her father, John.

Moving between different geographical locations, points in time, and subjective positions, the text operates both as a source of information about Thereza and her life as well as a distraction away from it.

The project combines photographs taken at locations associated with Thereza’s life with film stills and images sourced from internet searches; photographic representation oscillating between abstraction, pictorialism and illustrative literalism. The Curious Moaning of Kenfig Burrows explores the relationship between landscape and photography, particularly the mobilization of each as an aesthetic resource as well as a physical one, and the various cultural, political and practical uses to which they can be put. Focusing on a moment in the history of photography, both as a technical process, but also as a visual language, the project explores and expands the dialogue between individuals, institutions and other canonical orthodoxies that are asserted in contemporary life, and normalized through notions of custodianship, conservation and care.

IF YOU’D LIKE A COPY OF THE TEXT THAT’S PART OF THIS PROJECT (EMAIL OR POST) PLEASE GET IN TOUCH USING THE CONTACT FORM

The Curious Moaning of Kenfig Burrows - edited version

Where is it?

‘Underneath the car park at Caswell Bay’, comes the reply, and I think how I would like to discover it with her, to be guided by her experience and understanding, her matter of factness, her warmth.

I wait for her to continue but the question tails off.

Later she mentions that she does not want to be featured in my project, to appear in it in any way.

There are several photographs of the house under the carpark in the Dillwyn Llewelyn archive, which is held in a storage facility near Cardiff. The house has been photographed from the beach, limestone-marked moorland rising steeply up behind. Black gabled roof windows. A dark, vacant interior. It’s as if all the pictures have been taken on the same wintery day, variations on the same subject, a practice I recommend to my students.

‘Take many exposures, keep moving around,’ I might say towards the end of the day, as we sit at our patchwork of tables, a tangle of grey chairs lining the walls, the black out curtains hanging off their runners, swaying gently in the breeze.

Keep shifting your position in relation to your subject.

* * *

The house, Caswell Cottage, was built by Dillwyn Llewelyn as a holiday house for his family. I look it up on Wikipedia, and read an account of his grandson, John drowning there at the age of 12. I wonder how I can substantiate the details I read, and feel a sudden weariness at what will be involved; the documents, forms, appointments, acid free sleeves. Protective gloves.

* * *

Dillwyn Llewelyn took many photographs at Caswell Bay, some of which I encounter during my first visit to the archive.

Can we see the originals?

“Not today”

The cards are quietly passed around. I look diligently at each one but my attention is beginning to wander. I keep changing my mind about how I should be looking, oblivious to the multiple significances passing me by.

Should they stay in this order?

“Preferably. But don’t worry if they get a little bit muddled up.”

The images are already in a muddle and the information about them comes anecdotally, many of our questions with answers unknown. I’m finding it all quite difficult to process and perhaps by way of compensation, from time to time, I take my camera and make a picture of one of the pictures - stimulated more by what I know than by what is new.

A capture, but also, a refusal.

* * *

Here is a picture of a woman on a beach.

It’s Thereza and she is standing looking out to sea with a telescope. She holds it delicately, the eyepiece held in place with her right hand, her left hand gently supporting the extended weight of the optical tube. There is something incongruous about her Victorian dress, but of course it makes sense and there are other details I find more intriguing; that this young woman, a photographer, a scientist, with her aptitude, her talent, her opportunity and her inquisitiveness, is also a beloved daughter, subject of, and also subject to her father’s scrutinizing gaze.

* * *

A story starts to come to life, but is still partially obfuscated by anecdote, by the way certain narratives dominate, determined by the arbitrariness of who, or what survived. The house at Penllergare was demolished in the 60s, and council offices built on the site. While the observatory survived, the gardens fell into disrepair, the irrigation system failed, the roof of the orchid house fell in, the lake stagnated, the boathouse collapsed. People broke in, rode their bikes, lit fires, took drugs. The plans of the house and gardens were destroyed in a fire, bundles of lantern slides were abandoned in a ditch. And slowly the connection between subject, photograph, photographer begins to fall away; so much destruction, some casual, some by accident, just as it is about to become interesting. Just as it is about to be missed.

Some of Thereza’s diaries and papers are held at The British Library and I go there to read them. I switch between her diaries and memoirs, drawn into the separation between the two testimonies, written by the same hand, sixty-seven years apart. The diaries detail her day to day life; walks, marine curiosities found on the beach, the comings and goings of family, her developing interest in photography. She writes about a drop of milk, seen under a microscope, describing it as ‘a thin fluid, thickly filled’ with opaque white globules; a distinction drawn between the appearance of a substance to the naked eye and something more essential that can only be inferred through the lens of a microscope. The memoir is more reflective, evoking a different sense of time, an awareness of her family’s place in the history of photography, the burden of significance, the struggle to recall.

The diary starts on Thereza’s 22nd birthday when she was given a camera by her father My father, a doctor, gave me my first camera when I was a bit younger than she, about 15. The first photographs I took before then were with a camera belonging to him; a bulky tool with an oversized popper on its brown leather case. He kept it in his study, in a big cupboard that held other types of instrument, some dusty, some new, but apart from a stethoscope they were things without names, purposeful things, to do with his work, to do with looking inside.

Wikipedia again:

‘An otoscope is a medical device, which is used to look into the ear.’

I can still feel Dr Tuck in his consulting room describing the appearance of my eardrum, the source of all that pain, and the seepage of watery fluid that would stain the faded blue velvet cushion to which I pressed my poorly ear. My mum was worried I would go deaf with so many infections. I have never seen inside an ear, I can only imagine it, through his description, breathed into the side of my face as he gently pulls at the lobe of my ear… “ooh yes, very sore… red… flaky…. lacerated drum… pus…. Is that very tender…” as he pushed the cold metal device deep into the hot canal. And I would have nodded shyly that yes it was. ‘Tender’ is quite right, a word that can encapsulate such different kinds of sensation both given and received.

Years later my dad will go deaf and, for a while, the communication between us will completely break down.

* * *

The carpark at Caswell Bay is long and thin, fitting Thereza’s description of it as a ‘strip of land’ with a good garden, already there. The plot runs perpendicular to the beach, the white painted parking bays all facing forwards, towards the sea. In a shady corner is a visitor’s information panel, with its own little damp roof, spongy green swards of moss. In the library, weeks later, I find a list, made by Thereza, of trees planted not long after the cottage was built. A specimen of evergreen beech had thrived in the warm microclimate of the bay, and by 1878 was 17ft high and attracted ‘great attention from botanists’, but as I stand there looking up into the thick canopy of trees, seeking material echoes of that past; nothing.

The tide that afternoon is its lowest, flat sands stretching for miles to the west, shimmering pools of shallow water, the bright glare of the Bristol Channel in the distance. I find the river emerging from a drainage outlet that runs under the road, similar to the outlet of the River Llan as it enters the ‘picturesque landscape of Penllergare’, whose grounds are ‘topsliced’ by the M4 motorway. Further east along the M4, is Margam Castle, home of Thereza’s uncle. The house was built on the side of the mountain, a bleak landscape dissected and indented by ravines and rivers, small wooded valleys and black peat bogs. From that high up position overlooking the bay, they would know when a storm was approaching from the sound of the wind whistling up from Kenfig Burrows, a ‘curious moaning’ that was, according to her uncle, Kenfig Burrows ‘talking’ to Margam Mountain.

I Google Kenfig Burrow. It is now a nature reserve, managed by Bridgend County Council. There used to be a website, but its funding was cut, and then I find reviews of the beach in an online walker’s guide:

‘The wife and I spent a very pleasant couple of hours here Sunday afternoon. There were a couple of other unclothed men on the beach and one guy seemed to take a particular interest in my wife. I don't know if it’s normal for men to stare at women - it seemed a bit rude. But it didn't worry us and we enjoyed ourselves anyway... ‘

‘GREAT BEACH! Came here midweek, it was lovely. Walked naked along the designated beach. Had no problems with the usual ogling ... Probably about ten other nudes on the beach - didn't see any textiles.’

There’s a public facility near my home, an urban outdoor space; a resource with a reservoir, a bird reserve, a path for walkers. Nature in those environments can feel uncomfortable at times - you have to ignore certain features, keep looking away. Walking along the footpath one day, I find a black holdall by the side of the water. It seems displaced in such an ugly way, the associations with it being someone’s things, with it having been been gone through, violated. There are multiple openings - a black towel, ripped black plastic sheeting, and the broken zipper of the holdall itself all pulled apart to reveal the beautiful fur of a dog, absolutely still, a body completely engulfed by bag; wrong in so many ways.

I touch it gently with my foot, feel its weight. I take a picture, not knowing what else to do.

* * *

As well as photographs of the house, the archive holds many photographs taken on the beach at Caswell; Theresa by the waterline, and some others of her sitting on the rocks, in a different kind of pose, one that strikes me as conspicuous.

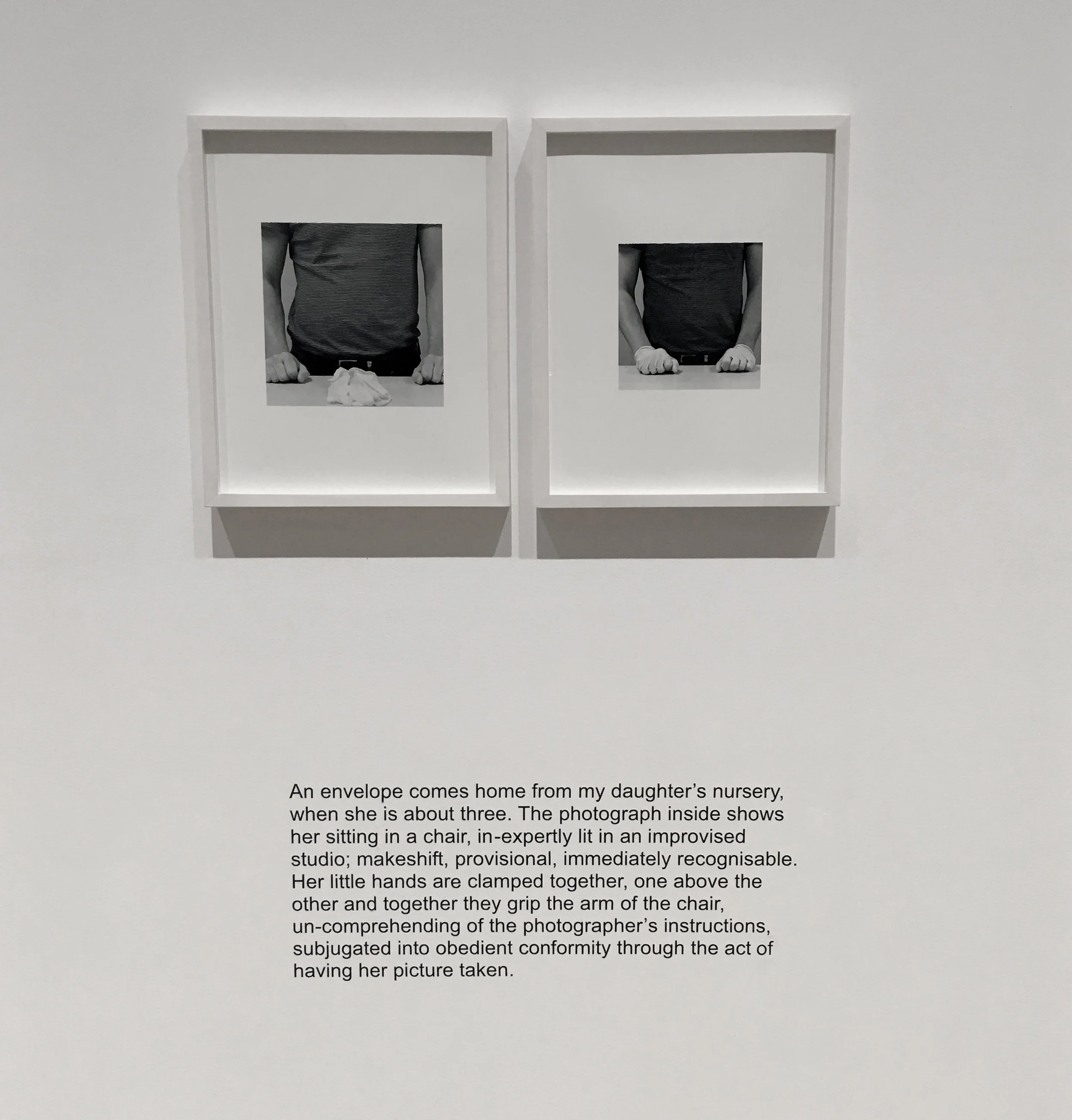

An envelope marked ‘photographs’ comes home from my daughter’s nursery one day, when she is about three. The picture inside shows her sitting in a rocking chair, in-expertly lit in an improvised studio; makeshift, provisional, immediately recognisable. Her little hands are clamped together, one above the other and together they grip the arm of the chair, un-comprehending of the photographer’s instructions, subjugated into obedient conformity through the act having her picture taken.

What are you doing in that photograph?

“Having my picture taken”

And there she has wandered accidentally into something beyond description that brings me back to Theresa, the way she is sitting; somewhere between a pose and the very real sense of her waiting, like a document slipping into something else, something more functional, both staged and not staged, depending on how it is understood.

I had an uneasy relationship with my daughter’s keyworker, the intimacy between us, something between neediness and distrust, the slippage between service provider and service user. Neither of us knew how to negotiate our relationship, how to navigate the terrain between accountability, tokenism and love. Our dialogue was mediated through the operational procedures of Camden Council Early Years Trust, that functioned as a kind of buffer, moderating expectations, neurosis, tone. Our daughter’s development was recorded on slips of paper by a variety of different hands, while we were at work, and she was left on an unfamiliar carpet, with scratched up CDs, chewed pens, dried pasta as playthings, some familiar from my own childhood nursery, the dimness of memory, and somewhere deep down, a return, an echo, a nightmare.

* * *

The idea of the house at Caswell being under the carpark stays with me, the sense of it as still there, like the bones of Richard III; a layer in the statigraphic column, haunted. I wonder if she will see me again, if she can be persuaded to be involved in the project after all, maybe just her hands. Walking along the river the last time I see her, we talk about the erosion of the riverbank, about how the river still bends and folds in much the same way that it would have done in Thereza’s time, its ebbs and flows subjecting the bank to the kind of forces of erosion that cause collapses, silting, small changes in its flow.

“It’s doing what rivers do” she says. I like her manner, her briskness, her knowledge, her understanding. Near the end of the walk, I ask if we might meet again, just one more time.

“Yes…”

She looks at me straight

“But I think you have it all.”